An Alice on the iPad iconographically consistent

Link iTunes

Arthur Rackham (born 1867 in London, died 1939 at Limpsfield, Surrey) was an outstanding illustrator who re-imagined a wide array of literary works and folk tales, mainly British, some European, for both children and adults.

His Alice In Wonderland illustrations were only a fraction of Arthur Rackham’s remarkable output. He belonged to that small group of artists, mostly British and American, who in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries created the illustrated children book as we know it today, including Walter Crane, Edward Lear, Randolph Caldecott, Kate Greenaway, Beatrix Potter, Edmund Dulac, E.H. Shepard and Kay Nielsen.

The aim of this project is to bring Rackham’s masterpiece to a wider public, which no longer has reason to remain bound to the rigidity of print. Looking at his work, it should be noted that shapes, scenarios, costumes and anatomical details of the fantastic figures, created through his rare sensitivity and visionary interpretation, have largely been turned into audio-visual representation throughout the past century. He has clearly influenced it, and continues to influence it, right up to the present day: in the physiognomy of innumerable characters, through shapes, proportions and colour research of costumes and scenarios. Especially in the fantastical representations of elves, goblins, mythological creatures and locations in the British and Northern European tradition. At the Walt Disney Studios, around the time of Rackham’s death, his illustrations inspired several elements of Snow White, not least the shapes of the enchanted trees. This diffusion process continues in some of the most recent cinematic productions: for example, the sirens, colours and backgrounds shades of the Black Lake of the Harry Potter movie adaptation, The Goblet of Fire, show the influence of Rackham’s illustrations for Undine. This is just one example among thousands. So it is quite natural to feel that his work circles out of the fixity of print. The force, the freshness and the dynamism of his illustrations still represent an interesting subject for extension into the digital. Some of the Alice scenes look almost as if they were already designed for audio-visual representation at the time of their execution, more than a century ago. For example, the illustration of the kitchen from the Pig and Pepper chapter. Can this really be called just a still image?

Rackham’s style is a meticulous investigation of the scene at dynamic moments in the story; the movement of bodies and scenic details seem to flow into the viewer’s eyes and to expand beyond the edges of the illustration. But in Alice in particular, he goes further, by enriching the illustrations with elements taken from contemporaneous daily life. The main character’s dress is taken directly from that of the young model, who had made it herself and had worn it for her first visit to Rackham’s studio. We are very far from the pasteboard models of John Tenniel, Alice’s first illustrator. Rackham’s Alice is keeping up with the new century, breaking with the traditional image that had restricted the heroine from her first appearance.

While Tenniel’s version is in perfect harmony with the text, this inherently brings its own limitations. Rackham shows that Alice can have a sensitivity and a vitality that transcend the Victorian nature of the first representation. Making her alive, closer to a child of the new century, and giving us for the first time an Alice who is interpretable, even conducive, to a different taste and open to new investigations.

The shock of the new was not immediately welcomed by everybody. The newspaper of the Establishment in London led the attack with a blistering review, which now seems absurd. The Times, 5 December 1907: ‘Tenniel was (Alice’s) predestined illustrator… [Arthur Rackham’s] humour is forced and derivative, and his work shows but few signs of true imaginative instinct… The best that can be hoped for is that neither Mr. Rackham or any other too adventurous draughtsman may venture further to experiment on Through the Looking Glass.’

‘Forced and derivative’ humour is probably what we would say nowadays about Tenniel’s illustrations.

The Application

Adapting the plates, a ‘pool of tears’

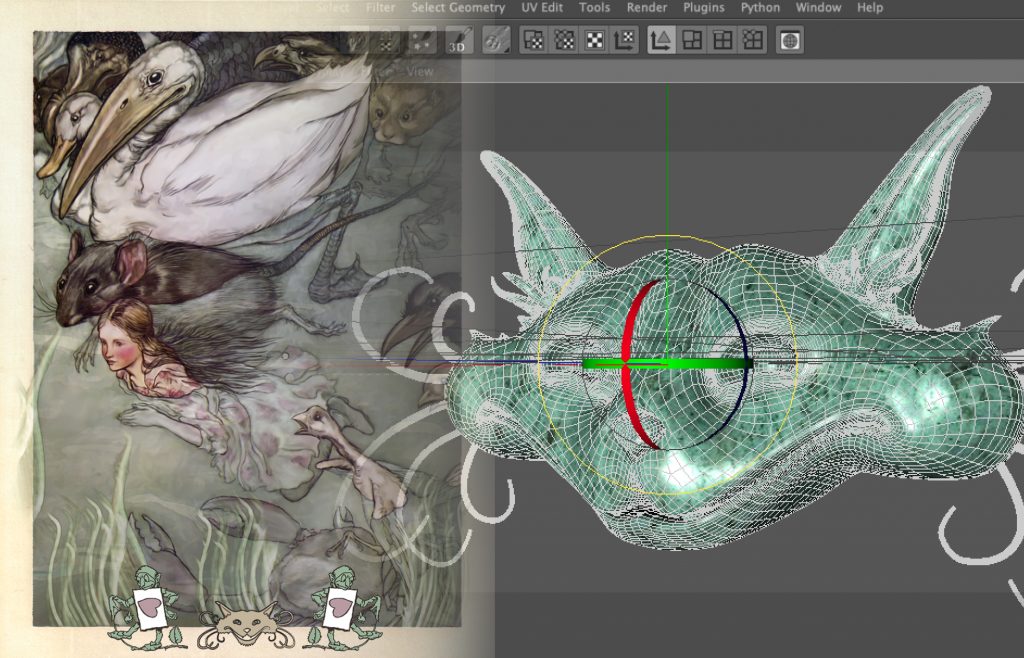

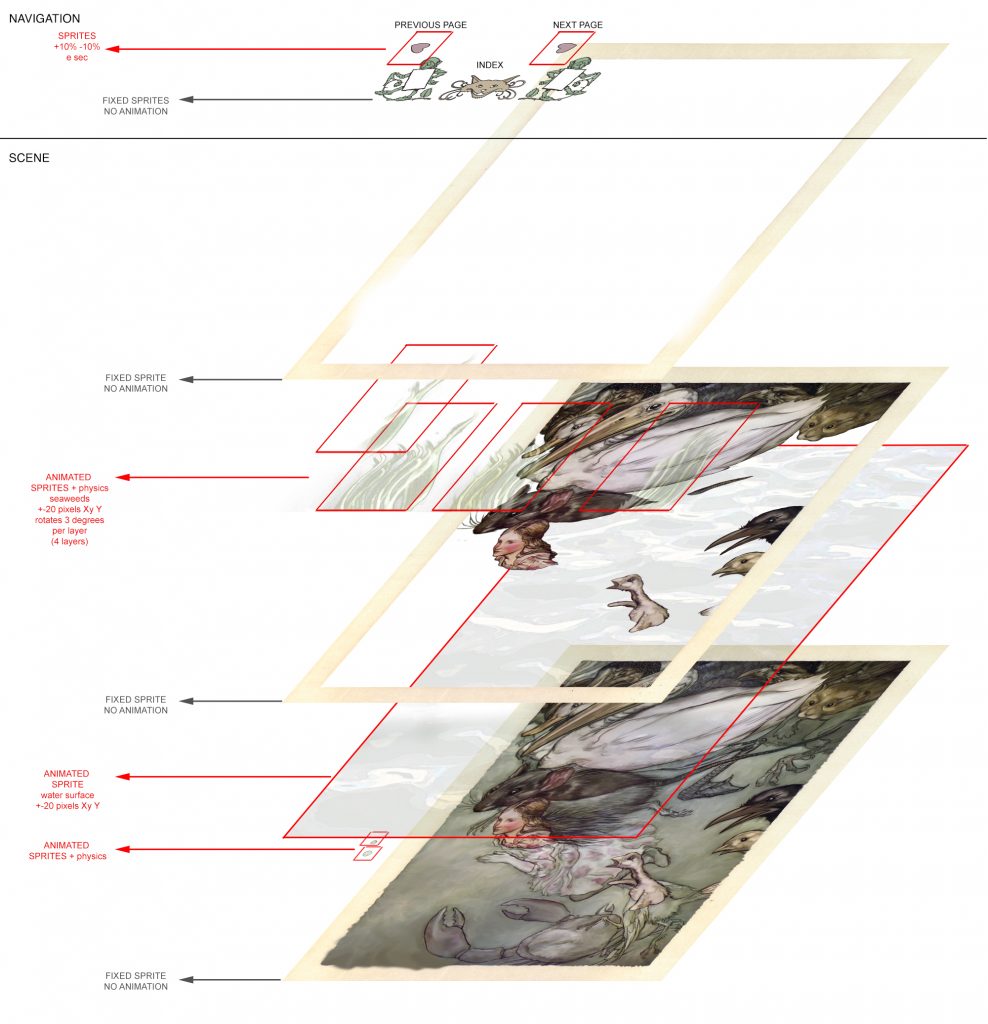

Adapting the illustrations hasn’t been easy. Firstly because of the constant fear of excessive intrusion into the original work. It is a constant dilemma for anyone who wants to deal with solutions that stretch so far from the original medium. This is not about experimentation, it is an attempt at updating a classic through a modern medium (one which would surely have fascinated Rackham himself if he had been alive in our times). Secondly, there are the practical and technical aspects; the difference in size between the boards and the laborious process of capture, clearing and preparation. The most difficult choices have been the interventions on the colours and the modification of some elements within the illustrations. Often reconstructed, cropping and detaching the original components into several layers meant that many new portions of the image had to be recreated. Although not immediately apparent, on the completed application over 20 per cent of the colour plates have been completely rebuilt.

Then it has been necessary to deal with the thorny issue of integration with outside elements, things not belonging to the original plate: insertions using details or textures obtained strictly from the same plate, parts taken from other illustrations in the same work and, in one case only, brand new elements designed and produced through the consultation of other Arthur Rackham’s works.

During all the phases of the adaptation of the plates great help has come from James Hamilton’s valuable monograph, Arthur Rackham, A Life With Illustration (Pavilion Books Limited 1990).

Sound design

The choice to enrich the interactive plates with audio tracks and original mixes happened almost naturally during the development of the application.

Looking at the pictures, we tried to imagine Alice’s key creative moments, its gestation as a text, 1856, and Rackham’s production, culminating in 1907. In both cases, periods when a lucky child’s ears could be filled with the noises of nature and spells of silence filled only with the sounds of the wind and birds. Years in which the soundscape in the countryside, far from London or any other growing European city, despite rapid industrialization, was not constantly corrupted by noise pollution.

We thought it would be exciting to build a link between this lost world of sounds and the illustrations. Just think of the context of the first adventures of Alice: a carefree afternoon spent by the little Liddell sisters in the company of the Rev Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a.k.a. Lewis Carroll, enjoying a boat trip in Oxford in July 1855. We can hear the sounds of propulsion across the water, of river birds, of a breeze brushing through the trees, without the incessant whine of any engine, the surreal ringtones of mobiles or the rise and fall of a humming plane in the distance (well, according to Astronomical and Meteorological Observations Made at the Radcliffe Observatory, Oxford Vol. 23, that particular day was rainy, but like Dodgson we can pretend that it was sunny). We searched for recordings made with absolutely no extraneous noise, from the authentic English countryside where achievable. In addition to this environmental sound, it is possible to play with extra sound effects which follow the text, when the characters themselves or the objects emits sounds described by the author, sounds which of course has never been linked to the illustrations for obvious technical reasons until today.

Accompanying the main menu navigation is a piece by Matthias von Holst (Gustav Holst’s great-grandfather), In a Cottage Near a Wood, rearranged for piano and classical guitar for the application.

Linguistic choice and original plates

Lewis Carroll’s text accompanying the work within the application is from the first edition in English and from the earliest translations for the other languages, according to first-publication dates: in France 1869, Germany 1869 and Italy 1871, and in the twentieth century in Spain 1922 and Portugal 1931. At the end of this introductory text are Rackham’s original plates, in their original proportions and frame as they appeared in the 1907 first edition, in reduced size at the center of the page. Giving users the opportunity of moving easily between two different ways of enjoying Rackham’s work, present and past, permitting as complete a view as possible of the extraordinary work that this great illustrator made with Carroll’s text. We hope at this stage you’ll meet a dimension of Alice still enjoyable across several levels and suitable for all ages.